ISIS is Going to Lose Raqqa

Header photo of Kurdish SDF fighters overlooking a post in northern Syria.

Raqqa, ISIS’ de facto capital in Syria, is going to be liberated within the next few months.

I’d written an article last year about ISIS’ outlook as a military presence in Iraq and Syria. My analysis at the time led me to the conclusion that contrary to their posturing, ISIS was a remarkably weak and under-qualified fighting force whose success emerged more from exploiting regional instability than from their skill and acumen as a martial entity. In short, they were reckless, lacking in discipline, tactically shortsighted, and staffed by idiots. Evil, but incompetent.

Largely because Americans have been distracted by our 2016 presidential election, which features a sentient toupee who keeps yelling about Mexicans, there’s been little mainstream reporting in the United States about how rapidly ISIS has been falling. Not only does it lack the simian theatrics of electoral politics, but covering ISIS’ disintegration in depth would force every hysterical media outlet to admit that the doomsaying about the jihadis’ invincibility amounted to little more than shameless fearmongering. The sensationalism and yammering pundits served their ratings-centric purpose, and now our broadcasting networks have tried clearing their throats and moving on.

Which isn’t to say that the Syrian and Iraqi civil wars have come to a close. The conflicts in the upper Levant are still grinding away, with ISIS behaving exactly as an overaggressive but disorganized flatlands militia would when facing superior opposition. There are certain situational fundamentals that have caused the jihadi insurgency to play out in rather predictable ways. ISIS’ increasing fragility and constant failures as a martial entity are little more than a rational outgrowth of patterns we’ve seen ever since they reached their territorial apex in 2014. And these very same factors will likely cause ISIS to lose control of Raqqa similar to how they’ve rapidly lost crucial supply lines and tactically valuable terrain over the intervening timeframe.

The largely Kurdish-Arab Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) have made remarkable gains against ISIS over the course of this year alone. The Kurds, along with Arab, Turkmen, and Syriac Christian allies, have been sustaining a highly successful campaign to oust ISIS from eastern Syria. Though ISIS utterly failed at breaking into Kurdish territory, they remain a menace to civilians and smaller holdouts throughout the region. Not only are the Kurds hungry to remove ISIS from neighboring terrain, but the local Sunni Arabs are also hoping to end the jihadis’ brutal occupation of central Syria. The SDF are closing further and further toward the Euphrates river, which remains largely within ISIS’ grasp.

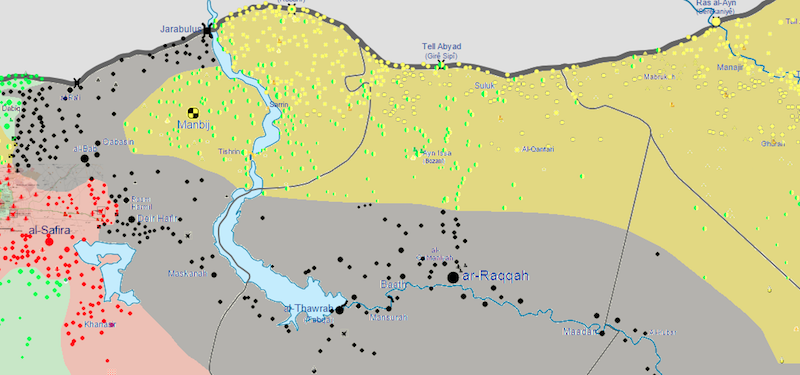

To give a quick rundown of how rapidly the SDF have advanced against ISIS, they’d only captured a small dent along the western side of Euphrates as of January 2016 (Kurdish-led forces first crossed the Euphrates from the east in December 2015). Within the past four months, the combined Kurdish-Arab forces have pushed across to the river’s western side and surrounded the key tactical holdout of Manbij. If you take a look at the Syria Livemap, you’re able to notice that not only have the SDF smothered and fully encircled Manbij, but the northern Euphrates leading into Turkey has been almost entirely stripped of ISIS control.

Once the Manbij operation is complete, the next objective is to cut south and liberate Raqqa - which has become ISIS’ de facto capital and was home to over 220,000 Syrians prior to the civil war. By my reading, ISIS is poised to lose the upcoming battle for Raqqa in what will amount to a shattering defeat.

While some observers might have lingering questions about the seriousness of the anti-ISIS coalition's intended push toward Raqqa, the United States began embedding special forces with Kurdish fighters over the past few weeks. Turkey's government, keeping steady on their renowned "Murder the Kurds" doctrine, has been bombing the Kurds for a considerable stretch of time despite Syrian Kurdistan's absence of reciprocal hostility toward Turkey. Now that American soldiers are fighting alongside them, Turkey can no longer bomb Kurdish positions without risking killing Americans. While deploying a small cadre of spec ops might seem unremarkable, it seems to serve a secondary purpose as a message that Turkey's attempts to undermine the anti-ISIS effort should immediately cease. Operations are reaching a critical juncture, with months of accumulated momentum about to roll down into central Syria.

The following map depicts territorial reach as of writing, with areas under Kurdish control highlighted in yellow and cities under ISIS occupation represented as black dots (territory in red is under the control of the Syrian government):

Map of the upper Euphrates and North-Central Syria - from Wikimedia Commons

To provide some background, Raqqa is the largest city along the Syrian stretch of the Euphrates river. Much of central Syria is barren, sparsely-occupied desert terrain - backwoods, if you will. The only place throughout that stretch of the country with heavy population aggregate is the Euphrates itself, which is home to a winding stretch of towns and hamlets that snake upward from the border with Iraq and right into Turkey. Raqqa is the largest municipality, and was the most pivotal city in ISIS’ forward capture when they began rolling through central Syria’s neglected, mostly rural terrain during their 2013-2014 expansion. As with the hinterlands of any country - including my own - that portion of Syria is generally conservative, sparsely populated, and poor.

It also made a prime target for a militia like ISIS that relied on sheer aggressiveness and speed in lieu of a more disciplined, methodical approach. If you examine the territory that ISIS managed to conquer, you come to the conclusion that the jihadis captured the terrain they did not because it was tactically prudent, but simply because it was the only land they could conceivably overrun.

That might seem like a pretty sharp leap in reasoning, but I think it holds considering reckless forward aggression was the exact same methodology they took when attempting to barge into Kurdish territory after conquering along the Euphrates. Their incursion into Syria’s Kurdish northeast displayed no modulation of tactics, simply a replication of that identical dumb aggression directed at a different front. This inability to adapt their operations while entering a new theater turned fatal during the pivotal battle of Kobane. I’ve written about the siege of Kobane before - I personally hold it as the single most important turning point in the early fight against ISIS - but the parameters of the battle bear repeating. In summary, ISIS attempted to deploy the full strength of their standing military against severely outnumbered and under-equipped Kurdish defenders holding the border town of Kobane back in fall 2014. The Kurds, being excellent guerrilla fighters, held Kobane from September 2014 to February 2015 until ISIS was so thoroughly bloodied they had no choice but to retreat. Various estimates outline that ISIS suffered losses equal to around 10% of their entire troop volume during the standoff. The jihadis seemed to have never fully recovered from what happened at Kobane, with that pivotal defeat ushering in their slow spiral as a military force.

Syrian Kurdistan, also known as Rojava, is somewhat more densely populated and urban in addition to being much more hilly and topographically uneven. It’s also home to an extremely skilled local defense force known as the People’s Protection Units, or YPG. The Kurdish YPG have a reputation as being hard, disciplined guerrillas who excel in small arms combat. They’re both cohesive and capable of adapting well to urban warfare. Which, in summary, made them perfectly suited to beating back a desert militia with little experience outside of shock advances across open flatlands. The YPG make up the backbone of the martial conglomerate known as the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), with approximately ~60% of their standing forces consisting of Kurdish fighters.

To return to Raqqa, what ISIS has been facing throughout the territory outside their capital is an inversion of what they witnessed during that failed attempt to invade Syrian Kurdistan. The SDF have been employing a highly methodical, efficient style of combat engagement that has allowed them to rapidly defeat the unorganized, demoralized ISIS fighters making a cursory attempt to hold onto Raqqa’s satellite villages. The Kurdish/Arab/Syriac Christian SDF forces have carried out the operation to liberate Manbij with typical intelligence and finesse. Not only have they encircled the city and prevented both retreat and reinforcement, but ISIS has suffered over 460 fatalities (some of these from coalition bombings) since the push to liberate the city began at the close of May 2016. As a point of comparison, the SDF have lost just around 90 fighters.

What’s interesting and important to note is that the SDF detachment spearheading the advance into Manbij is majority Arab. Various claims place the anti-ISIS force consisting of well over 2,000 Arab fighters and only a few hundred Kurdish guerrillas. While the ethnic makeup of the combatants might bear little relevance during the immediate fighting (and certain statements might undersell the number of Kurdish fighters), it portends the likelihood that Arab authorities will govern Manbij once the city is wrested from jihadi control. The newly established de facto Syrian Kurdish state of Rojava has gone to painstaking lengths to foster sectarian cooperation and multi-ethnic governance, and Kurdish authorities tend to encourage Arab self-rule in newly liberated regions.

That last bit is crucial. While relations might be mending in the most tentative of ways, there’s long been mistrust and tension between Kurds and Arabs. Territory liberated by the SDF typically falls under the jurisdiction of the Syrian Kurdish state, and granting Arab populations autonomy tends to foster stability and cooperation as well as safeguard against cross-ethnic resentment. It also provides a template for what might happen when the SDF oust ISIS from further territory throughout central Syria - the regions join Syrian Kurdistan while local charters remain respectful of Arab self-rule.

In terms of martial arithmetic, what we’ve seen in Manbij is an impressively rapid and lethal advance. That level of westward progress in such a small span of time, coupled with high enemy fatalities, suggests that ISIS has lost their ability to put up much of a fight at all. And this has as much to do with their crippling deficiencies as a fighting force as it does with the structural problems ISIS has been facing in terms of managing their territory and resources. It’s also a standing demonstration of the situational realities that will predict the outcome of future offenses against the jihadis - including the upcoming fight for Raqqa.

As a sidenote - the Syrian Kurdish-led SDF conglomerate has not lost a single major battle against ISIS since their inception. Not one. Which outlines that not only are the Kurdish YPG (and the SDF as a whole) a far superior fighting force, but that they’re also prudent in terms of which battles they fight at which moments and how they stage their operations. On the other hand, ISIS has a marked tendency to barrel into areas of instability while offering little in the way of opposition against determined opponents. When Kurdish forces began bearing down on the occupied city of Sinjar in late 2015, ISIS put up about two days’ worth of resistance before cutting their losses and fleeing the region.

The consequence of this strategy is that ISIS has lost a remarkable amount of both fighters and territory over the past few months. An apparent disinterest in staging effective defense means that ISIS tends to lose threatened territory pretty rapidly, as well as suffer sizable casualties in the process. This simultaneous habit of throwing aggression at newfound fronts to compensate against these losses leads to ISIS bearing pretty heavy fatalities on that end as well - employing a blind shock-trooper methodology of advance against prepared opponents means that you often hurt yourself far more than you do your designated enemies. With the Kurds in particular, the process often resembles someone trying to backhand a porcupine.

To break down the relevant numbers around both the Kurdish-led advance and ISIS’ current station as a martial power, the SDF have around 80,000 active fighters in Syria - with <a href="http://www.businessinsider.com/syrian-kurds-now-say-they-now-control-territory-the-size-of-qatar-and-kuwait-combined-2015-8?IR=T target="_blank">about 50,000 coming from the Kurdish YPG. ISIS allegedly has only 19,000-25,000 active fighters spread between Syria and Iraq, which represents a 20% plummet in personnel since their peak in 2014.

The jihadis also appear uninterested in (and incapable of) recuperating troop losses in the upper Levant, as ISIS began encouraging foreign fighters to filter into the more vulnerable theater in Libya in lieu of Syria late last year. Per usual, ISIS is forsaking areas overrun with tough opposition in favor of a more fragile, less challenging military front. The subtext behind this slow pivot toward Libya is that the jihadis seem well aware of how bleak their outlook is along the Euphrates. Ordering recruits to wholesale avoid the Syrian front is a pretty telling, fatalistic admission. This withering of martial resources is further exacerbated by the fact that the operation to liberate Manbij will likely result in ISIS losing their last direct supply line into Turkey - a transfer route that has already become strained over the past year.

And while I’ve focused more on the capabilities and troop volume of the SDF, ISIS might be facing Bashar al Assad’s Syrian Arab Army as government-affiliated forces near Raqqa from the east. I’ll touch more on this later, but the essence of the matter is that ISIS’ could well be forced to extend their already depleted and worn-down military across two separate fronts.

The broader, more thematic variables that will cause ISIS to lose Raqqa can be understood along three parameters - flaws in ISIS’ military structure, the nature of their opponents, and particulars relating to local management and resources.

The first of those I’ve covered to a point, but it bears repeating just how wounded ISIS is in terms of infantry command. Not only do they demonstrate a persistent lack of tactical cohesion, but ISIS has been facing crippling issues with morale and even paying their fighters at all. Desertions have long been such a problem that ISIS set up a standalone police force designed solely for capturing or executing those attempting to flee. However, this policy has allegedly been rolled back in a desperate attempt to discourage further desertions and demoralization. It was a scattered, frankly incoherent about-face that points to simultaneous confusion and ignorance about the basics of sustaining a military effort. Reports also indicate that not only is ISIS unable to pay many of their recruits, but that large portions of their territory are effectively undergoing famine. It’s a horrorshow of an environment not just for those suffering under ISIS occupation, but for their militants as well.

Jordan Matson, an American who fought with Kurdish YPG during crucial early battles, made explicit comments during a BBC interview that the morale and competence of jihadi fighters degraded rapidly over his time on the ISIS front.

The jihadis seemed to have spent their most skilled foreign recruits - many of whom were vicious Chechen fighters - during their failed push to overtake Kobane. With ISIS having lost their more competent shock troops to earlier fights against the Kurds, they’re now down to the dregs. Jihadis aren’t typically the smartest guys around, and their flunkies tend to be a particularly useless bunch.

This all intertwines with the dysfunction inherent to ISIS’ structural management. The jihadis apparently ignored the most basic questions about financial management and resource generation during their low-rent blitzkrieg into the neglected badlands of the upper Levant. Their only persistent source of native income has come from oil sales, and none of their standing territory had the requisite infrastructure to produce and distribute the necessary volume of agricultural products on a fully self-sufficient basis. The inevitable result has been deprivation. “Inevitable” being the key word - ISIS set themselves up to become some kind of ersatz state that was bound to both perpetual hostilities with its neighbors and complete economic isolation. The starvation and financial suffocation we’re seeing right now was an almost certain outcome.

This is a problem that the sharper observers of the jihadi insurgency have been noting for months. Eli Berman, a talented scholar of terrorism and rebel movements, put this succinctly in an article he wrote for Politico.com in late 2015. ISIS has a severe problem with sustainable funding, as black market oil has been their only consistent source of revenue. Except not only do they lack the engineering expertise to sustain petroleum extraction, but their various refineries and extraction points are being ruthlessly bombed. In addition, there’s widespread discontent among those living under ISIS’ rule. This has, in turn, resulted in civilians fleeing en masse and an unceasing hemorrhage of human capital. ISIS is suffering from a severe deficit of doctors, engineers and technicians, an absence that has only becomes more severe with time. Berman manages to articulate what prescient analysts have called from the beginning - the architecture of the self-proclaimed Caliphate rendered it a failed state upon its inception.

The aforementioned factors are endemic, and were a widespread problem even before ISIS started facing growing military pressure across multiple fronts. What we’re seeing at this juncture is ISIS being savaged by both internal dysfunction and heavy military opposition. The jihadis could potentially limp along in terms of holding territory as long as opposing forces weren’t cutting too aggressively toward their key holdings. Except at this point ISIS is facing a vice-like pincer from opponents in both Syria and Iraq - the Iraqi National Army just liberated the key city of Fallujah. It’s a phenomenon I predicted back in 2015, a type of walls-closing-in suffocation that would only exacerbate ISIS’ howling vulnerabilities and capacity for self-destruction.

And this brings me to the third of those listed factors - the factions ISIS is up against. During the earlier days of the anti-ISIS advance, the Kurds were the only forces making determined inroads. As 2015 rolled to a close and 2016 continues, the respective militaries of the Syrian and Iraqi governments have also started ousted ISIS from occupied territory - with the Iraqi national army shoving ISIS from Ramadi and the Syrian Arab Army liberating Palmyra. And as I mentioned before, the official Syrian Arab Army has advanced into greater Raqqa province from the west simultaneous to the Kurdish advance from the northeast.

This all points back to my core thesis about what ISIS represents as an insurgency. In so few words, ISIS’ seeming success came from overextending themselves during a timeframe when their opposition was too distracted or disorganized to mount sufficient resistance. They took huge risks when other militias of their caliber might be tempted to follow a more measured route, leaving ISIS severely unprepared to deal with situational changes. If your martial doctrine depends on localized instability and blind aggression, then it leaves you highly vulnerable should opposition marshall against you or shock advances no longer prove tenable. Emphasizing reckless forward capture without any coherent plans to either manage or safeguard your newfound territory also leaves you open to incompetent defense and managerial self-sabotage. There’s that old adage about how “an army marches on its stomach”, but the outlook is even grimmer for a militia that’s forced to defend vulnerable territory while not only starving, but facing aerial bombardment and well-prepared, highly motivated opposition. Fighters whose only experience comes from undisciplined shock advances tend to do very poorly when forced to shrink back and defend, especially when serious airpower is near-constantly shelling their position.

Even a cursory examination of the martial arithmetic suggests there’s no way ISIS will be able to hold Raqqa in the long run. And similar to their defensive collapse at holdouts ranging from Palmyra to Ramadi and Sinjar, their defeat will probably look less like a determined standoff and much more like a sort of martial wilting. ISIS has spent months on end spitting farcical threats of ruination at the United States and Europe, and they have a persistent habit of puffing themselves up against far more powerful entities. It’s just that when these powerful factions are your neighbors, they’ll eventually kick down your door.

There’s an excellent graphic from the New York Times that lays out the breadth of terrain ISIS has lost throughout both Iraq and Syria. If you examine the dates of each respective defeat, you’ll notice the rapidity with which the jihadis started losing territory beginning in Spring 2015. The New York Times report outlines that ISIS has lost nearly 50% of its territory in Syria since its August 2014 peak as well as 20% of its holdings in Iraq. The only contiguous spread of terrain they retained uninterrupted control of until recently was the Euphrates, which allowed ISIS to sustain the dual transfer of foreign recruits and black market oil. Except with the jihadis now near-completely ousted from the river’s northern stretch, they’re on the brink of losing that lifeline as well.

And while ISIS has fared poorly against the Kurds and Kurdish-led forces since the beginning, they've done terribly against quite literally everyone as of late. Standing tallies indicate ISIS hasn't won a single major battle in the past year - including against enemies they'd previously routed like the Iraqi National Army. When even opponents you once defeated start bowling you over like you're the skinny kid in gym class, it might be time to make like that old Blue Öyster Cult song and try not to fear the reaper.

Examining prior battlefield performance and ISIS’ inherent difficulty in holding key cities, it’s easier to frame Raqqa’s liberation not in terms of “if”, but of “when”. ISIS’ accumulated failures tend to have a sort of compounding effect - the more territory and resources they lose, the further it exacerbates their already vulnerable position. The lingering difficulty will lie not in defeating ISIS, but in repairing both the structural ruin and sectarian animosity left in their wake. While ISIS gave horrifying conduit to Sunni resentment, multiple reports indicate that Shia militias have visited murder upon Sunni civilians throughout Iraq as well. These same rancorous paroxysms persist in Syria, and the Shia-Sunni hatreds will seethe and writhe well after Raqqa falls. The only enduring “victory” ISIS could be said to have achieved was the mass inflaming of ethno-sectarian tensions. Jihadism, after all, is deeply reactionary, and few things are more reactionary than attempting to stoke the old antagonisms. It’s a tragedy writ large and spilled across the upper Levant, ensuring primordial hatreds continue to stalk the flatlands like a bloodied revenant even after ISIS dies.

Adam Patterson can be reached by email at "napalmintheAM@gmail.com" or on Twitter @AdamPattersonDC.