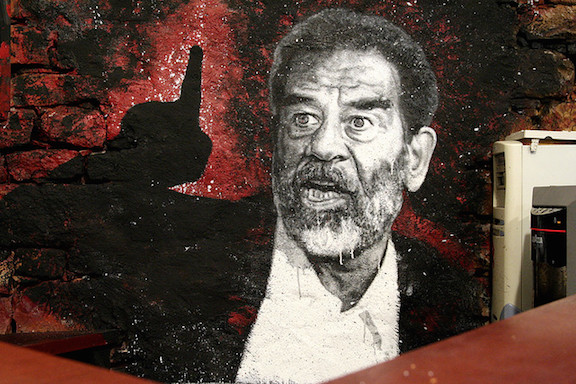

Saddam's Ashes: The Roots of Iraqi Insurgency

ISIS’s rise as a local power was near inevitable considering the discord thrown at their feet. The 2003 invasion of Iraq ripped the sutures from an already fractious and bloodied country, one so endemic with suppressed violence that only the presence of a glowering tyrant warded off sectarian revolt. Similarly, the corrosion of Assad’s rule in Syria exposed decades of stewing animosity that fed upon itself as the regime lost control. Above anything else, it was these ruptures that ignited the Sunni insurgency.

This essay is both prologue and coda to my previous two posts. It’s a prologue in the sense it outlines a thesis for why ISIS became so powerful, and it’s a coda in the sense it forecasts the regional strife that will persist after ISIS has scattered. ISIS has behaved like the demonic id of two war-ravaged states, acting out their deepest sectarian hatreds. But it also displayed traits atypical of the greater insurgency - broad foreign recruitment, grandiose self-promotion, doomsday ideology, and a pornographic fixation with beheading. The unifying elements fueling regional upheaval are both subtler and more insidious.

ISIS is built upon contradictory pathologies. They reject modernity while promoting themselves online. They ban intoxicants despite evidence of stimulant abuse in their ranks. They compel modesty and rape female captives. They draw recruits with a tenuous grasp of scripture, yet hold themselves as harbingers of a prophesied apocalypse. It’s these inconsistencies, along with ISIS's rapid ascent, that can make it so elusive to us in the West.

The rantings of ISIS's recruiters are pure Salafist firebreathing, all verbal pyrotechnics designed to sway the angry and directionless. They speak of divine calling, vengeance, and the end of days. But ISIS emerged from the same factors as as all newfound militia in the region, namely the localized scourge of sectarian grievance and war-induced deprivation.

This brings me to my ambivalence about Graeme Wood’s piece in The Atlantic, where he posits ISIS as rising primarily from a sincere (albeit disturbed) religious faith. He seems to nail their ideology pretty cleanly, but the factors enabling violent insurgency are often far less celestial. If anything, much of ISIS’s expansion can be credited to the aftershocks of dismantling Saddam’s regime and its Sunni hegemony. As certain analysts have pointed out, much of ISIS’s top leadership are refugees from Saddam's Baath party. Though near-exclusively Sunni, the Baath party was more of a thuggish incarnation of political dominance than a junta built from Islamist fervor.

Political elites, especially those sustained through violence, are jealous custodians of their own power. This impulse can be so sadistic and paranoid that it manifests as victimizing the disenfranchised - witness Saddam’s longstanding persecution of Iraq’s Kurdish minority. But Iraq’s Sunnis themselves are a clear minority, and the Baath party’s brutality was often a campaign to keep the beaten Shia majority in line. It’s not dissimilar from the behavior of apartheid regimes like that of post-colonial South Africa.

Our 2003 invasion completely inverted Iraq's political order. The Baathists were beaten back and scattered, and Saddam died twitching on a rope as his Shia executioners yelled abuse. The Baath party was summarily outlawed, and America gave explicit favoritism to Iraq’s majority Shia - likely a stilted attempt at fostering majoritarian rule.

ISIS is not a nationalist force, as are the YPG of Kurdistan who train fighters of all creeds and shelter threatened minorities. It’s a genocide-minded, virulently sectarian monster that has a tendency to drive all non-Sunni from its territory. And despite its supposed internationalism, there's clear evidence that foreign fighters are exploited as front-line grunts who take the brunt of military assaults.

Like the territory it sprang from, ISIS is a complex and occasionally self-contradictory synthesis. Its origins lie in a patchwork collection of grievances, sectarian rancor, political instability, and fractured power balances. And despite their adherence to Jihadist eschatology, religious particularities are its least resounding traits. If anything, their doomsday fixation and deranged Salafism are a self-contained characteristic. A bloody, unhinged conflict can yield bloody, unhinged religiosity, but it’s an isolated byproducted rather than a cross-regional motive.

Reports suggest that the majority of ISIS’s leadership consists of Iraqis, particularly those from Saddam’s former regime. In a sense, the previous regime consolidated under a facton that allowed them to recapture some of their thuggish supremacy. Iraq’s arrogant and sadistic pre-invasion elite has transformed into an arrogant and sadistic insurgent power. It’s also become clear that Syrian and Iraqi nationals are given preference in terms of leadership appointments. Ethnic nepotism has been a key factor in shaping ISIS’s hierarchy from the outset.

Additionally, ISIS has managed to instill some local stability. This is most pronounced in their supplying necessities throughout deprived territory. In places torn by conflict, economic fracture is typical and exchange of goods exists in a legal grey zone - one that often is secured under violence. ISIS has also made sincere attempts to legitimize itself, and has rebuilt utilities that went unmanaged following the 2003 invasion. On a purely pragmatic level, ISIS answered the gasping need for firm oversight in neglected Sunni areas. Though the finer points of state building may elude them, they’ve done a functional job with upkeep.

Which brings us back to their founding leadership. Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi (born Ibrahim al-Badri) - ISIS's self-anointed calpih - was detained for ten months under U.S. holding at the Camp Bucca center in 2004. It's an ugly admission to make, but our detention centers produced monsters where none might have existed. Not only did the renditions stoke hostility among local Sunni, but they also consolidated some of the region's most spiteful malcontents under the same roof. It's been theorized that al-Baghdadi underwent his fabled radicalization while held at Camp Bucca, where he was detained with a cadre of future ISIS leaders.

It's also important to note that the city of Baghdad underwent a mass Sunni expulsion following the collapse of Saddam's regime. Al-Baghdadi himself took his nom de guerre as a bitter reminder of this lost home. Baghdad, once a majority-Sunni city, has seen all remaining Sunni forcibly pushed to the far-west suburbs around Fallujah. Coincidentally, Fallujah is the closest territory ISIS has ever captured near Baghdad. A new Shia elite now reigns over the capital, and their rule is preceded by a hateful remembrance of the cruetly that Saddam's cabal visited upon them when they were in power. This has been coupled with brutal reprisals against local Sunni.

This ties back to one of ISIS's core contradictions. To an extent, ISIS is a privileged organization enabled by deprivation. While the seeds of ISIS's creation lie in the tearing asunder of Iraq and the radicalization that ensued, the more rote aspects of its functioning fall back on old power structures. Not only is much of its middle-tier leadership merely a transcription of the old Baathist autocracy, but many of its foreign recruits are products of comfortable backgrounds.

"Jihadi John", the deranged ISIS theater kid who has starred in many of its western-tailored beheading videos, is apparently the child of upper middle-class London professionals. In fact, he planned to celebrate his graduation from university with a full safari in Tanzania. He represents the strange nexus that defines much of ISIS's core - wartime loss and violence meeting in the middle with sustained privilege. Some of their uppermost leadership are figures with unremarkable backgrounds, which likely helps propel a myth of a universalist, class-blind Jihad. The same can be said for most of their shock troops. The breadth of their command, however, seems to represent old entitlement transcribed.

This also might explain the reported discontent within ISIS's ranks. As I noted in a previous post, there was apparently a recent clash between Chechen and Tunisian ISIS brigades in Syria. But we never hear about these flareups from Iraqi or Syrian recruits. These folks are on familiar turf, and they seem dead set on asserting power in their homeland.

This is markedly different from how previous Islamists - including both al-Qaeda and the Taliban - were primarily concerned with driving foreign influence from self-proclaimed Muslim lands. ISIS, on the other hand, is focused on reforming territory and consolidating a Sunni dominance across Iraq and Syria. It’s a fundamentally localized, sectarian militia whose tactical objectives address internecine grievances inflamed by political destabilization. Its creed is distinctly Sunni, an effective veneer for enticing angry young men with its grandiose claims. But war is typically a materialistic game, and religiosity is a durable means of imposing order and conviction within a disparate group. Though sincere, their ideology seems more of an accelerator than a root cause.

The ripping open of neighbor states that are currently occupied by unpopular (and in Assad's case, brutal) Shia regimes created a shared power vacuum that practically demanded the emergence of a belligerent Sunni force. The overwhelming amount of Syrian-local rebel factions are also Sunni, and are known to make temporary pacts with ISIS in light of threats from Assad's forces. Considering the Shia hegemony within both governments, there seems no immediate solution for the disenfranchisement of the local Sunni and the lapsed custody within their enclaves.

The sundering of Iraq and Syria left an opening for Salafist extremism to grab a new foothold, and it’s unlikely this will dissipate with the breaking of ISIS. Absolutist religion can be dangerously appealing in unstable regions, especially when inflamed by fear and sectarian bitterness. It remains to be seen how deeply this will bleed into the national character.

In the long run, ISIS is probably doomed. There are far too many factors stacked against them. However, secondary developments, not the conditions endemic to war-ravaged Iraq and Syria, will be their undoing. The berserk hostility toward their neighbors, the political isolation, and the reckless overextension are all ingredients for collapse. Some of these are carryovers from Saddam's Iraq, others emerged from long-standing Jihadi agitations. But the circumstances that enabled their rise will persist after this particular outgrowth has been cauterized. If the sectarian hatreds fester and the people suffer under shattered infrastructure, then the Levant will continue to simmer.