Yemen: Terror Adores a Vacuum

If there's one thing we've learned since Iraq's mode of governance was forcibly changed from "brutal dictatorship" to "violent sectarianism", it's that terrorism thrives in power vacuums. The American memory is notoriously short, but our misadventure in Iraq was a tactical failure of such apocalyptic proportions that it's practically a crime in and of itself that its architects haven't faced judicial reckoning. But power and influence can buy you many things, the most corrupting of which might be legal immunity.

The United States barreled into Iraq less than two years after the largest terror attack in our history. The rationale for our invasion was unsettlingly amenable - shifting between arguments that Iraq had nuclear armaments and/or that the sitting Baathist regime was an aggressive supporter of international terror. The first of those, as has been exhaustingly noted, was a lie. The question around Iraq becoming a hotbed for international terrorism ended up being more of an ugly, self-fulling prophecy.

There's been a lot of discussion - much of it hyperbolic - about whether or not our 43rd president and his inner circle should be prosecuted. I'm not about to, nor do I have the qualifications to, mount any legal arguments in either direction. But no one ended up being a more sincere and supportive friend of terror than the junta of smirking neocons who shoved Iraq into a state of sectarian massacre. In effect, the Bush administration created the perfect stew of conditions for the rise of ISIS, and then stiffed the American people with a nearly trillion-dollar tab to watch the equation unfold in real time. As has been noted by operatives and analysts with far more authority than myself, our 2003 invasion may have midwifed the entire modern jihadi movement. Without it, violent Islamism could have been a shadow of what it is today.

The only lesson that can be taken from this - if you can call something so bloody and despairing a lesson - is that we now have an exhaustive portrait for the conditions under which substate terror can flourish. As an echo to what's happened in Iraq, we're observing a similar unraveling in Yemen. However, as was arguably the case in Syria, this implosion occurred without western military action. The conditions that enabled terrorist agitation in Yemen are coming largely from within, and can be credited to a different sequence of events from what happened in Iraq. The consequences, however, are similar.

Unlike the more wealthy and diplomatically connected Arab nations, Yemen has remained alien from the uneven modernization that has visited countries like Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. It lacks the energy reserves and geographic positioning to capture the attention of either the west or China, and has long dwelled in a place of diplomatic oblivion, being largely ignored by the world's powers in its peninsular seat overlooking the Horn of Africa. And with this comes a lack of economic preeminence that can otherwise provide stability in more autocratic governments.

Frank Herbert allegedly based the Fremen of his Dune series off an amalgamation of Muslim peoples throughout the Middle East. When reading Dune, I remember facetiously thinking of the Fremen as “Space Kurds”, though looking back this was a mischaracterization. The Kurds are far too cosmopolitan and outward-looking to pass for the insular and harsh desert people of Herbert’s universe. The Kurds are a multi-sectarian populace and many are proclaimed socialists. The closest analogue, if we’re to choose a singular ethnic group, would probably be the natives of Yemen.

One of the failures of commenters like Ayan Hirsi Ali is that in their monochrome censure of ‘Islam’ and ‘the Muslim World’, they completely mislead their Anglophone audience to how multifaceted the Middle East is in its sectarian, ethnic, and cultural divisions. Iran, for example, is the inheritor of hundreds of years of Persian history and has remained resolute in its rejection of Arab political influence. The Iranian brand of Shia Islam is more somber, even mournful, than the fanatic Salafism of ISIS and their ilk. Shia around the world publicly flog themselves with chains in observance of the annual Day of Ashura, a ritual which emphasizes that our world is fallen and martyrs are the only righteous men to ever walk this plane of sorrow and corruption. This practice is, of course, widely denigrated in Sunni-dominant Saudi Arabia.

While us Yankees know Saudi Arabia for its strident and misogynist Wahhabism, we forget to note how staggeringly rich the Saudi kingdom is. It’s drenched in oil money, and while their women can’t drive, it’s not uncommon for their men to own sports cars. It’s frequently an ostentatious place, one whose royal family broadcasts a gaudy fusion of imperial wealth and regal pomp. The oil business has been good to the Saudis, and the place has grown fat with the abrupt explosion of its energy sector. Saudi Arabia might be rooted in local tradition and fundamentalist religion, but it’s thoroughly modern in its bloated wealth and privileged sons posting their Maseratis on Instagram. To make a crude analogy, Saudi Arabia is Texas with prayer rugs.

Yemen has no such consolations. It’s an inward, harsh place, one so far removed from the asynchronous modernization of its neighbor that it has become a source of fixation for Sunni revivalists. While compulsions to modesty and gender separation are a cultural standard, you’re less likely to see Yemeni women in the ornate veils sometimes worn in Saudi cities. The Yemenis cover themselves in nothing more than undecorated black. It gives the impression that Saudi Arabia’s niqabs are less about preserving modesty and more about a performative, almost theatrical show of modesty. The Yemeni Shia, lacking both the extreme wealth and the arrogant Wahhabism of the Saudi kingdom, do not bear these conceits. They merely sustain their traditions within an impoverished, tribal quietude.

The parallels between Yemen and Iraq lie not in cultural similarities, but in the simultaneous explosion of sectarian violence and breakdown in civil authority. Substate violence requires divisive antagonism by default, and nothing works as a more effective catalyst than religious and ethnic separation. To use an old metaphor, if violence and scarcity are the flint, then sectarian resentment is the kindling. Weakness in government and economic oversight only augment the likelihood of violent rupture. It also happens to be an alluring cocktail for groups whose modus operandi involves exploiting substate instability.

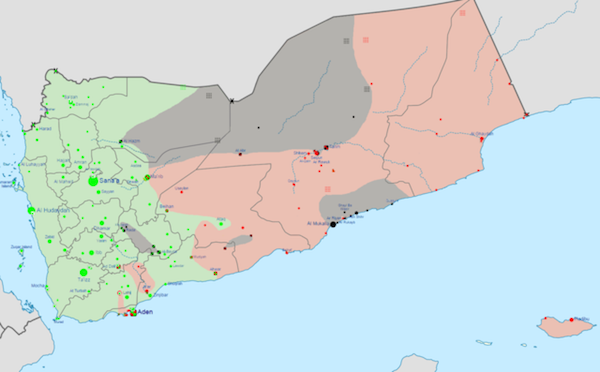

Yemen has been undergoing an escalating civil crisis since 2011, when much of the population began to <a href=http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-1229586">revolt against the endemic corruption of the regime of president Ali Abdullah Saleh. Saleh is a devotee of Shia Islam, and has allegedly worked behind the scenes to foment agitation among Yemen's distinctly Shia Houthi rebel faction since stepping down in 2012. His successor was his Sunni vice president Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi, a figurehead who remained in power until January 2015 when the Houthis overtook the presidential palace. Shia Houthis now control the western reaches of the state (including the former capital at Sanaa). Sunni loyalists occupy the east, and swear fealty to Hadi - who currently resides in exile in Saudi Arabia. Hadi has blessed the ongoing Saudi bombing campaign against Shia Houthi militia, something that has been met with vicious condemnation from Iran.

Yemen's population is near-universally muslim, with ~55% of the population following Sunni Islam and 45% following various Shia permutations. As of April 2015, untold thousands of Yemenis have perished in the conflict, a figure that doesn't account for the vast civilian displacement and the martial chaos that have emerged in its wake.

And this is where, like clockwork, terrorist factions spill in. Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula had been attempting to gain a foothold in Yemen since the late '90s, and the government eventually began cracking down on Al-Qaeda in 2001. The standing Shia government eventually declared open war on Al-Qaeda in 2010, but when revolution broke out in 2011 Al-Qaeda managed to exploit the newfound anarchy and began capturing increasingly significant holdouts. This pattern of guerrilla warfare and terror tactics continues unabated, with Al-Qaeda having captured the city of Al Mukalla in April of this year while Shia Houthi forces were preoccupied with engaging Sunni forces from Saudi Arabia. Terrorist factions across the Middle East are near-incapable of gaining territory in the midst of civil stability, so their default tactics have fallen back on attempting to escalate local disorder to the point where the cracks in oversight become pronounced enough to exploit. And it doesn't hurt that, like ISIS in Iraq, many of Al-Qaeda's territorial gains occurred throughout rigidly Sunni territory.

And never a group to miss out on easy opportunity, there's evidence that ISIS is trying its hand in the ongoing Yemeni land grab. While ISIS have proven themselves to be a noisy and theatrical bunch, far more skilled at chest-beating and exaggeration than effective operations, they appear to be infiltrating the more unstable parts of Yemen. Inevitably, they just released one of their Jihadi pageant videos, threatening vengeance against the Yemeni Shia and declaring an intent to claim territory for local Sunni. If anything, they're possibly attempting to garner sympathy from a rancorous Sunni populace, similar to how they managed to move through much of Sunni Iraq unimpeded.

To employ American boardroom jargon, ISIS's swinging away from their defeats in Iraq and Syria to focus on gains in Yemen is the terrorist equivalent of a corporate "pivot". It's the mark of a group that's trying to surmount failures in one region by pursuing secondary opportunities in another. The resistance from Kurds and local Shia in Iraq and Syria has proven to be fatal to ISIS's success, and there's little bluster to be found in throwing bodies at tactical failures. Clueless young men with a romanticized image of violence and holy war are much more easily swayed by promises of (if only transient) conquest, and Yemen can at least offer potential for as much now that the country has reached newfound instability.

As far as local outlook is concerned, this is a hazier conflict to predict that what we've witnessed in Iraq. Inevitably, fighting has broken down along Shia/Sunni lines, with analysts suggesting that the antagonistic Saudi-Iranian puppet show has resumed in new form with the countries throwing military assistance at opposing sides in the conflict. And this is ultimately where the political compass will point for the foreseeable future across the core of the Middle East. We're looking at a revival in Sunni supremacism, with regional terrorism acting as its sword arm.

Jihadist terror has become markedly localized, with foreign hit-and-run incidents like 9/11 and the downing of Pan Am Flight 103 falling out of fashion in favor of grabbing territorial footholds. The earlier generation of Bin Ladinist cells were preoccupied with instigating symbolic acts of violence in the hopes they'd intimidate (or at least push away) western powers. In the wake of localized instability and the collapse of authoritarian regimes, terror factions have prioritized claiming large swaths of territory amidst the chaos, mutating into open militias in the process. ISIS and Al Qaeada's current iterations are much more hellbent on putting boots on necks, and seem more actively antagonistic toward local Shia than they are toward the proverbial "crusaders". In their self-mythologizing, they fancy themselves conquerors where they once fabled themselves liberators.

This will likely spill into the diplomacy (or the lack thereof) between local powers. Exempting the long-standing Hezbollah cells in Palestine and Lebanon, the vast majority of modern terror organizations in the Middle East are Sunni. Iraq, Syria, and Yemen all currently house Shia regimes who are facing active insurgency from Sunni organizations, many of them increasingly well-organized and hellbent on establishing sectarian dominance. There's also speculation that many of these Sunni militias are receiving assistance from the Saudi Kingdom. In light of this, we may witness Saudi Arabia and Iran exercise their longstanding antipathy through playing chess with external conflicts. We may see a closer marriage of terror and state power than ever before, culminating in a region-spanning internecine standoff. And when this breaks, the security of national boundaries will be more illusory than ever.